photo credit: Hugo Glendinning & Gavin Rodgers / click for hi-res version

photo credit: Brett Rubin & Bernard Benant / click for hi-res version

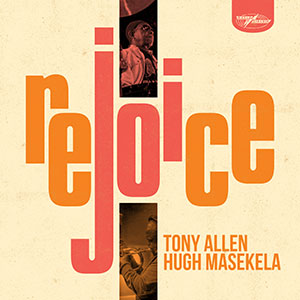

Tony Allen & Hugh Masekela

Rejoice

Every now and then a recording collaboration between a pair of master musicians achieves a resonating synergy. Whether it be in the world of jazz (think Thelonius Monk with John Coltrane, or Don Cherry & Pharoah Sanders), or African music (Ali Farka Touré & Toumani Diabaté) – these are timeless, dual-helmed masterpieces that seem to rise above considerations of culture, geography or genre to achieve a universality, bewitching a significant international audience in the process.

To that beguiling inventory can surely be added a new entry in the shape of Tony Allen and Hugh Masekela’s beautiful and compelling Rejoice, a spirit dance of an album on which these two globally revered African cultural icons fuse their time-honed talents, on drums and flugelhorn respectively, into a spontaneous, celebration of friendship and untrammelled musical possibility, melding elements of West African rhythm and improv jazz into a truly unique album.

Although completed in summer 2019, initial recording for the album, with World Circuit producer Nick Gold, took place as long ago as 2010 at north London’s Livingston Studios (where Gold had previously captured such gems as Ali Farka Touré and Toumani Diabaté’s Ali & Toumani and Orchestra Baobab’s Specialist In All Styles). The protracted hiatus was the product of no single issue other than the refusal of the planets, and Messrs’ Allen and Masekela’s hectic respective international schedules, to align. The seeds for the album go back even further. Masekela had long held a fascination with Afrobeat rhythms while Allen maintained a passion for African groove and Afro-jazz. Their 2010 convocation was in fact the culmination of many conversations over several decades. Tony Allen explains, “I first proposed the idea of working with Hugh in 1984 in London, just before I moved to France. Eventually we were in the same place at the same time, it just happened to be over a couple of decades later!”

Nick Gold was instrumental in finally getting the pair in front of the microphones. “Tony told me that he and Hugh had been talking about doing an album together when we were recording [Allen’s 2009 World Circuit album] Secret Agent. To cut a long story short, we saw that the two of them were going to be in Europe at the same time, so we booked a weekend in the studio in London. They both said that’s all they needed.”

Rejoice is the first posthumous release from Hugh Masekela, who passed away in early 2018, aged 78, and stands as a memorial to this most jubilant and beloved musician. Renowned as an African musician of global stature, with more than 40 albums to his name, Masekela’s pervasive inspiration and weighty legacy, both as an artist and as a political figure, have few parallels in a pan-African context.

Although their paths had crossed before, Masekela and Allen’s long-standing friendship was first secured while they were both appearing, at separate times, at FESTAC 77, the month-long World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, staged in Lagos at the beginning of 1977. A hugely significant event, boasting many thousands of Black cultural practitioners representing over 50 African countries as well as the wider African diaspora, FESTAC 77 was instrumental in propelling burgeoning Pan-African consciousness onto a wider international stage, building on the platform of the first World Festival of Black Arts, which had taken place in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966.

Rejoice can be seen, then, as the long overdue confluence of two mighty African musical rivers – a union of two free-flowing souls for whom borders, whether physical or stylistic, are things to pass through or ignore completely. Propelled by Allen’s buoyant, ambidextrous rhythms and etched with Masekela’s mellifluous, heart-swelling horn blowing and exhilarated vocal chants, the album’s eight elated, transporting tracks embrace elements of Afrobeat and township jazz but just as readily blur generic lines, so that they occupy their own uniquely uninhibited aesthetic space. According to Allen, the album deals in “a kind of South African-Nigerian swing-jazz stew” – a description borne out by even a cursory earful of the gorgeous parallel harmony horn hook and loping drums of ‘Agbada Bougou’, the propulsive percussive swing and loquacious brass chatter of Coconut Jam or the skittering snare drums and optimistic fanfaronades of Obama Shuffle Blues (“The Obama thing was still new when we first recorded together”, says Allen, explaining the song’s title. “Hugh was responsible for naming all the tracks at the end of the session, and he really wanted to get Obama in there…”).

The music’s apparently effortless swing is, of course, hard-won by its venerable creators’ decades of practice and similarly towering instrumental techniques, but Rejoice succeeds not as a showcase for virtuosic ‘chops’ per se, but as an ingenuous exercise in mutual musical joie de vivre, one that speaks as much to the duo’s shared free-spiritedness as to their equally peerless technical skills. Indeed, it’s an album that should appeal as much to fans of similarly unhindered contemporary near-jazz genre-benders like Ezra Collective, The Comet Is Coming or Moses Boyd’s Exodus as much as to aficionados of established West African or South African styles. It’s something underpinned by the presence on the album of younger musicians, such as keyboardist Joe Armon-Jones (Ezra Collective), bassists Mutale Chashi (Kokoroko) and Tom Herbert (Acoustic Ladyland/Polar Bear), and vibes player Lewis Wright, alongside the more seasoned, sometime Jazz Warrior sax player Steve Williamson.

Hugh Masekela’s nephew, Mabusha Masekela, something of a ‘backstage baby’ who grew up with his uncle in both the US and in West Africa, sheds light on this cross-generational connection. “One of the great qualities about my uncle is that he was a genuinely timeless person”, he explains. “He liked to get involved in what other musicians were doing but his playing was always beyond trends. There are young people out there now who have cottoned on to Huey’s sound, and that’s because whatever he laid down just doesn’t really date.”

Masekela’s horn playing on Rejoice more than bears this out. His liquid, lyrical melodies are an instantly recognisable signature, a seductive combination of improvisational élan and meticulous note placement, always dovetailing skilfully with Allen’s bustling cadences. Recording had commenced with Allen playing the drums unaccompanied – indeed, nothing was pre-written before the duo entered the studio. “Every track was direct and spontaneous”, Allen confirms. “It was just Hugh, the bass player and me. Every time I changed my drum programme, that was the signal to start a new track.” Nick Gold confirms the extemporaneous approach. “The studio had two recording rooms, so we set Tony up in one room and he would play a pattern for as long as he wanted. He was doing a lot of light and shade within that, especially on the snare and hi hats, so it was already very musical. He would then give it to Hugh who would work out a melodic structure in the other room, and then he’d blow on it. After that they’d look at possible bass parts. Towards the end I suggested they do something literally together. That didn’t really work – I hadn’t realised how much Hugh was sculpting his parts.”

As well as blowing exquisite flugelhorn, Masekela was also inspired to overdub some spontaneous vocals on a trio of numbers, either deploying colloquial Zulu, as on the seductively loose-limbed opening track, ‘Robbers, Thugs and Muggers’, with its earworm chant of “O Galajani” – township slang for any such collective of rogues – or, as on the self-explanatory and appropriately jazz-meets-Afrobeat-hued tribute to Fela Kuti ‘Never (Lagos Never Gonna Be The Same)’, in English. “As soon as we laid down the melody, Hugh immediately wanted to sing”, says Allen of the latter song. “He was singing for his friend. He and Fela were close – they had a lot in common. It was a friendship even more than a musical thing, and, yes, of course, they were both political animals…”

Masekela’s long-time percussionist, Francis Fuster, is a good friend of Allen’s and also knew Fela Kuti well. “Fela and Hugh had a lot of respect for each other; I am proud to say I knew both gentlemen, and I loved them equally. They were similarly important figures, just representing different parts of Africa. Fela was more aggressive in his political beliefs, while Hugh was more patient, but they were striving for the same goal in terms of freedom and opportunity for African people.”

Masekela’s final vocal contribution appears on the gloriously named ‘Jabulani (Rejoice, Here Comes Tony)’. In addition to supplying the album with its title, the lyric, teased across the cat-like mooch of the duo’s playing, encapsulates the comradely spirit of the record: “Jabulani Nang’u Tony/ E’Shay Izighubhu/ U Ya Zi Gevoza/ U Ya Zi Dhabula” (“Be happy, here is Tony/Playing the drums/He is hitting them hard/He is blasting them!”). In addition to ‘blasting’ those skins, Allen also contributes a hushed but celebratory, semi-spoken commentary to the closing track, ‘We’ve Landed’ (“Tony Allen, Hugh Masekela / Check it out!”), one of the final elements to be added to the album.

Crucially, the finishing touches are very much what Allen and Masekela had planned to add after the original 2010 tracking was completed. “The feeling was really good”, Allen recalls of those initial sessions. “All of us were thinking we were going to follow it up with overdubs of percussion, keyboards, voices and so on. It was an exciting idea.” Unfortunately, diarising those studio dates would prove problematic, even though Masekela and Allen would regularly bump into one another on the European festival circuit. “I would meet Hugh when we played together in places like Helsinki and Copenhagen”, Allen recalls. “Every time we met he would ask me, ‘What’s happening with this project’? I had to say, ‘I don’t know!’ Eventually I asked Nick if I could hear the tapes, and that started the project back up again. Unfortunately, Hugh passed away soon after.”

In the summer of 2019 Allen and Gold were back in the studio finally directing the long-delayed finishing touches. Masekela was there, if only in essence, too. “When Steve Williamson was recording his sax parts he said he could feel the spirits rising out of Hugh’s playing”, remembers Gold, who was also eager to remain faithful to the album’s initial conception. “When we’d started the record, both Hugh and Tony agreed that they wanted as simple a sound as possible; so when we were finishing we kept things minimal. It’s a very open record – there’s a huge amount of space in the tracks. There’s no guitar. It’s basically drums, flugelhorn and bass, with a bit of colouring from saxophone on three songs and some hints of keys and vibes. What’s nice is that there’s loads of space for Tony. With the full-on Afrobeat thing there’s usually a lot of additional percussion; even on Fela’s tracks, Tony’s drums can be quite buried.”

Allen pronounces himself very happy with the finished album and remains phlegmatic about its protracted gestation. “Ten years is a long time from beginning to end of [making] an album, but my own philosophy is that everything eventually appears at the right time, for a reason…” He also has plans to tour the album but is, of course, faced with the problem of filling his departed friend’s considerable shoes. “Hugh, for me, is a one-off – I don’t think I ever heard another South African play quite like him”, Allen acknowledges. “His way of playing was way out. His solos were unique; it was like he was speaking his own language through his horn. Having said that, if we do get to play these songs, I want the trumpet player to be a South African with a South African quality. I don’t care where the rest of the musicians come from. This won’t be a Tony Allen concert; I want it to be a tribute to Hugh, just as this album is a tribute to him.”

Hugh Masekela

Born in the township of Kwa-Guqa, Witbank, a coal mining settlement near Johannesburg, the young Hugh Ramapolo Masekela was inspired to play trumpet by the 1950 Kirk Douglas film Young Man With a Horn and immediately excelled on the instrument. Encouraged to perform by anti-apartheid activist Trevor Huddleston (through whose auspices the young Masekela received a gift of a brand new trumpet from none other than jazz superstar Louis Armstrong), by the late ‘50s, Masekela was making his name playing with South African bebop combo the Jazz Epistles, with whom he would cut the country’s first jazz album. He would also play in the band for the hit musical King Kong, billed as an ‘all-African jazz opera’, featuring the country’s most renowned female singer, Miriam Makeba, who Masekela would later marry. In 1960, he would leave an increasingly acrimonious South Africa, first for London and then New York, where he enrolled in the Manhattan School of Music and immersed himself in the jazz scene, later settling in California. Hits like easy-paced 1968 instrumental chart topper ‘Grazing in the Grass’, produced by his long-term producer, partner and friend, Stewart Levine, an appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival and a guest slot on The Byrds’ ‘So You Want to Be a Rock’n’Roll Star’ helped turn Masekela into a pop celebrity, but at the same time exposure to militant Black US politics and the wider counterculture radicalized him, and after more than a decade in exile he returned to Africa.

In 1973, Masekela spent time in Zaire, Liberia, Ghana, and Lagos, Nigeria, where he stayed for a month with the similarly politicised Fela Ransome-Kuti, who duly introduced him to the traditional West African music-based Ghanaian/Nigerian band OJAH, with whom he recorded and later toured in the US. A fellow trumpeter before he took up his signature sax, Fela Kuti’s influence on Masekela would remain pervasive (Masekela would have a hit with his 1984 version of the Fela classic, ‘Lady’, recorded around the time he and Allen were first discussing collaboration and designed to raise funds for Allen’s erstwhile bandleader, then languishing in a Lagos jail). Together with Levine, Masekela would stage the Zaire ‘74 concerts that preceded the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ Kinshasa boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, and he would later settle in Botswana. Anti-apartheid protest songs like ‘Soweto Blues’ (1976) and ‘Bring Him Back Home (Nelson Mandela)’ (1987) would keep Masekela’s name front and centre in South Africa, even if his presence on Paul Simon’s 1987 Graceland tour was regarded as controversial in some circles. After the fall of apartheid, he would finally return to his homeland and become a mainstay of its musical landscape once again while continuing to record and tour the globe. In 2010 Masekela received his country’s highest honour, the Order of Ikhamanga.

Tony Allen

Born in 1940 in Lagos and now residing in Paris, Tony Oladipo Allen, now a sprightly, indefatigable 79, is, in an equally influential figure, most notably as the defining rhythmic engine of the aforementioned Fela Kuti’s sprawling Africa 70 combo – the much-celebrated lodestar of Nigerian Afrobeat.

Like Masekela, Allen cut his teeth listening to and playing jazz. Influenced by American drummers like Art Blakey and Max Roach as well as Ghanaian percussionist Guy Warren (also a member of OJAH), he was playing with a number of Lagos jazz and highlife bands when he made the acquaintance of Fela Kuti, whom he would accompany for the next 15 years – first as part of Fela’s Koola Lobitos, and later as part of Africa 70, for which they developed a new musical language, fusing West African rhythms, American funk and jazz into what would later be dubbed Afrobeat.

Allen’s simultaneously kinetic yet counter-intuitive drumming has underpinned an extensive catalogue of superb solo works, including a series of classic afrobeat LPs produced by Fela in the 70s, his 1999 avant garde opus ‘Black Voices’, ‘Film of Life’ (featuring the dazzling masterpiece single ‘Go Back’, a collaboration with Damon Albarn), and his 2017 EP release, a tribute to his hero Art Blakey.

He remains a prodigiously engaged and much in-demand musician, having created innumerable, groove-heavy coalitions with an astonishingly diverse retinue of collaborators that include everyone from Damon Albarn (their shared adventures over the past 2 decades started with the 2002 album ‘Home Cooking’, and has continued with alt-rock supergroup The Good, The Bad and the Queen), Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sebastian Tellier, Grace Jones, Malian singer Oumou Sangaré (a firm favourite of Masekela’s) and more recently, Detroit techno legend Jeff Mills (their “Tomorrow Comes The Harvest” project was released on Blue Note in 2018). ■

For more information, please contact Joe Cohen or Carla Sacks at Sacks & Co., 212.741.1000,